Settling into Life in Rome

A little over two months have passed since elections in Italy, in which the relatively newcomer party Brothers of Italy (FdI) came in first with 26% of the vote, a remarkable increase from the 4.4% it won in 2018. On October 22nd, almost a month after her election, Giorgia Meloni became the first female prime minister of Italy. She heads a center-right coalition consisting of the nativist League (Lega) and the center-right Forward Italy (FI) parties. Including 237 of the 400 seats in the Chamber of Deputies (140 of which are held by FdI members) and 116 of the 206 seats in the Senate, Meloni’s coalition has a supermajority of the seats in parliament (with 63 held by FdI members).

When it comes to the Meloni administration, what do we know so far? So far, Meloni’s administration has been conservative without being radical, reiterating the country’s commitment to international alliances like NATO and domestic priorities like strong families and low inflation. But she also faces a number of challenges, both domestic and foreign, that make it difficult for Italy to govern.

Problems in the Economy

The new prime minister faces two distinct problems as soon as he or she assumes office. She faces both internal pressures due to an unwieldy coalition and external headwinds, such as a projected slowdown in growth (while GDP growth was stronger than expected in 2022, economic growth is expected to sharply decline to merely 0.3% in 2023). Meloni’s administration has been shaped by these intersecting forces, which have already prioritised addressing rising energy prices, regulating immigration, and guaranteeing Italy’s access to EU COVID recovery funds.

Meloni’s first international trip as prime minister was to Brussels, where Italy is hoping to secure a continuation of regular disbursements of €200 billion in EU recovery funds (of which it has thus far received €67 billion) through 2026, contingent upon the country’s successful implementation of reforms and the achievement of EU-mandated spending targets. Additionally, in regards to energy, Italy has been successful in decreasing its gas imports from Russia, with imports from Russia making up only 10% of Italy’s total imports in September, down from 40% in February. In addition, as of the beginning of November, its storage facilities were already at 95% capacity, more than enough to see the country through the winter.

In 2022, Russian gas was used to fill these storage facilities; in 2023, it will be necessary for the planned replacement sources to come online without many hiccups in order to repeat the feat. Over the course of the summer, the previous Draghi administration actively pursued new supply, signing agreements with several countries, including Algeria (Algerian gas exports to Italy are expected to double by 2024). The success of the Meloni government in seeing the completion of a regasification facility planned in Piombino is crucial to the country’s ability to import energy; the facility is scheduled to open in the spring of 2019, but it is being challenged in court by the city of Piombino.

The initial budget of the Meloni administration focused heavily on rising energy prices. The budget, which must be passed by the end of the year, includes a tax increase on energy companies, a reduction in the so-called citizens’ wage, a minimum income programme that the coalition believes discourages work, and tax deductions and bonuses totaling €21 billion to help households and businesses cope with the high cost of electricity. The left has been screaming about these proposed cuts. The prime minister, who has previously identified as a woman, a mother, an Italian, and a Christian, included measures in the budget to encourage people to have more children, such as reducing taxes on baby products and increasing benefits for children.

Problematic Allies in the Coalition and a Diplomatic Scandal

Meloni has encountered difficulties within her own government as a result of problems sparked by her coalition partners. Lega leader Matteo Salvini (through ally and Interior Minister Matteo Piantedosi) has pushed migration back to the forefront of the national agenda, which contributed to an early diplomatic kerfuffle with France. He has also advocated for a bridge connecting Sicily with mainland Italy, which is included in the government’s budget.

Italy has closed its ports to NGO ships in the Mediterranean, arguing that the countries from which the ships are flagged should take responsibility for the migrants on board. There were protests in Paris last November because Italy denied entry to an NGO ship, which was then sent to France. France, like Italy, continues to struggle with the sensitive topic of immigration. As part of a migrant redistribution pact facilitated by the EU, France was supposed to take in 3,500 people from Italy. While the voluntary redistribution plan was expected to relocate 8,000 migrants from Italy, as of before the diplomatic dust up, only 117 had been successfully relocated. Italian President Sergio Mattarella, who has good relations with French President Emmanuel Macron, stepped in to defuse the diplomatic spat between his countries. His hard work seems to have paid off: As of late November, France and Italy have agreed to establish bilateral working groups and collaborate in strategic sectors including automotive, energy, and steel.

Remember that 2022 was a big year for emigration from both the United States and Europe. The number of asylum requests received by the European Union in August was the highest for the month since 2016. 95,000 migrants arrived in Italy by boat in 2022 (up from 63,000 in 2021), putting a strain on resources and highlighting Europe’s continued inability to effectively deal with a migrant crisis that began on land and at sea in 2015. Controversy has persisted over the role of NGO ships in Mediterranean patrols. Since many of these ships operate so close to the North African coast, their critics say they amount to a de facto ferry service, encouraging people smugglers to dump their human cargo into unsafe boats, safe in the knowledge that they will likely be rescued by NGO vessels not far from the coast and brought to Europe.

As part of a programme organised by Christian organisations, Italy accepted 114 migrants from Libya last week and flew them to the country via aeroplane. “We say no to human smugglers and yes to a path that leads to integration,” Italian Foreign Minister Antonio Tajani said. The onset of winter has slowed the pace at which migrants are seeking Italian shores via the sea lanes, but the issue of migration will remain in Italy as relevant as ever, due to both Salvini’s interest and the reality on the ground.

The Area of International Relations

The Meloni government is advocating for a stronger Italian voice in the region in order to secure and maintain increased energy supplies from North Africa and to stem the flow of illegal migration. In unveiling her policy this week, Meloni aimed to promote Italy as an intermediary between Africa and Europe, one that lacks the problematic history that other European countries have had with the continent. Italy, she said, would adopt a “non-predatory but collaborative posture,” an obvious jab at France. Despite the fact that Italy lacks the resources to displace France as the leading Western actor in francophone Sahel (the coastal regions of Libya, Tunisia, and Algeria), the country is still likely to push for a greater role in the region.

On Italy’s position vis-a-vis U.S. great power rivals, I was optimistic before the election, writing in Discourse, “Reading the tea leaves of a potential FdI-led government leads one to conclude Italy could, in the best-case scenario for the U.S., find itself with an administration that takes a robust stance against China and Russia in the framework of an overall transatlanticist approach.” Meloni has taken a firm stance in favour of Ukraine, declaring upon taking office that Italy would “continue to be a reliable partner of NATO in supporting Ukraine.” The cabinet signed off on a decree last week that would allow the government to provide arms to Ukraine over the course of the next year without seeking individual parliamentary approval for each donation (the decree itself however will still need to be approved by parliament). Italian media have reported that the SAMP/T tactical anti-missile system or the older Skyguard-Aspide air defence missile system will likely be included in the deliveries of arms to Ukraine.

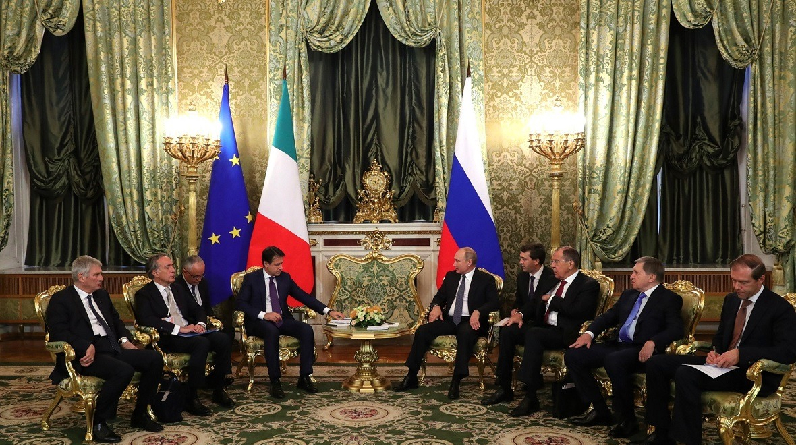

Meloni has stuck to her word on supporting Ukraine despite pressure from within and without her coalition. If the coalition partners of FdI had been in charge, Ukraine’s situation would have been handled very differently. It is common knowledge that Lega is sympathetic to Russia and that its leader, Matteo Salvini, openly admires Vladimir Putin. Silvio Berlusconi, leader of FI, is a close personal friend of Putin’s and has worked to improve ties between the two countries. The friendship between Berlusconi and the Russian dictator once again came into the spotlight when a recording of the former Italian prime minister surfaced in which he said Putin had reconnected with him and “sent me 20 bottles of vodka and a really sweet letter for my birthday.” This was just days before Meloni took over the government. In return, I sent 20 bottles of Lambrusco (a sparkling Italian red wine) and a similarly mushy letter. It didn’t take long for the EU Commission to rule that the vodka bottles presented to Berlusconi were in violation of EU sanctions (however, it is up to individual nations to implement them).

The new administration was severely embarrassed by the news just before its investiture. The Italian Prime Minister responded, “Italy will never be the weak link of the West with us in government.” Even though FdI is currently dictating U.S. policy toward Ukraine, its coalition partners’ pro-Russian stances will almost certainly resurface at some point in the future when they may feel more prepared to challenge FdI’s leadership. This is a place where they could work with populist parties like the Five Star Movement (M5S): Former Prime Minister and current M5S President Giuseppe Conte has called for Italy to press for negotiations to end the war and has backed a recent wave of largely left-wing protests in Italy against the war and the supply of Italian arms to Ukraine. As a result, while Meloni’s government can count on continued strong support from Italians for Ukraine in the short term, if public opinion on material support for Ukraine continues to deteriorate, it could become a wedge issue and threaten to bring down the coalition (and it has never been particularly strong in Italy).

Washington hopes that an Italian government will be willing to take a firmer line on China, in addition to alignment on support for Ukraine. In this regard, it is still not clear what course of action the Meloni government will take. Although Prime Minister Meloni has been critical of Beijing in the past and during his campaign, he recently met with Chinese President Xi Jinping on the sidelines of the G20 and advocated for stronger trade ties between the two countries. This is an early indicator that the economic implications of tamping down ties with China may ultimately outweigh other considerations.

See Also: The Tennis World Is Getting More Men Wearing Italian Style From Uomo Sport

A recent report by a Spanish NGO confirmed that China maintains the highest number of illegal “police stations” in Italy of any country in the world. China has opened “police stations” all over the world ostensibly to “tackle transnational crime and to provide administrative services to Chinese nationals abroad, such as renewing drivers’ licences abroad and other consular services.” Sometimes operating under the guise of fake charities, their goal is to monitor and retaliate against Chinese citizens living abroad who are critical of the government.

The FBI is currently looking into Chinese stations in the United States, and Director Christopher Wray said last month that China’s actions “violates sovereignty and circumvents standard judicial and law enforcement cooperation processes.” As with many other European nations, especially those facing economic uncertainty, Italy sees China’s economic power as a powerful disincentive to stray too far into the camp of a more strident China policy, but it is still far too early to tell what shape the Meloni government’s China policy will take.

While Giorgia Meloni’s administration is still in its infancy, two things are already apparent. First, the government is not “far-right,” despite the fact that a lot of ink has been wasted on that label. Rather, it is a conservative government that pursues conservative rather than radical policy goals. Second, even with a parliamentary majority, it is difficult to govern Italy due to the country’s tumultuous coalition partners and the country’s sluggish economy.

Leave a reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.